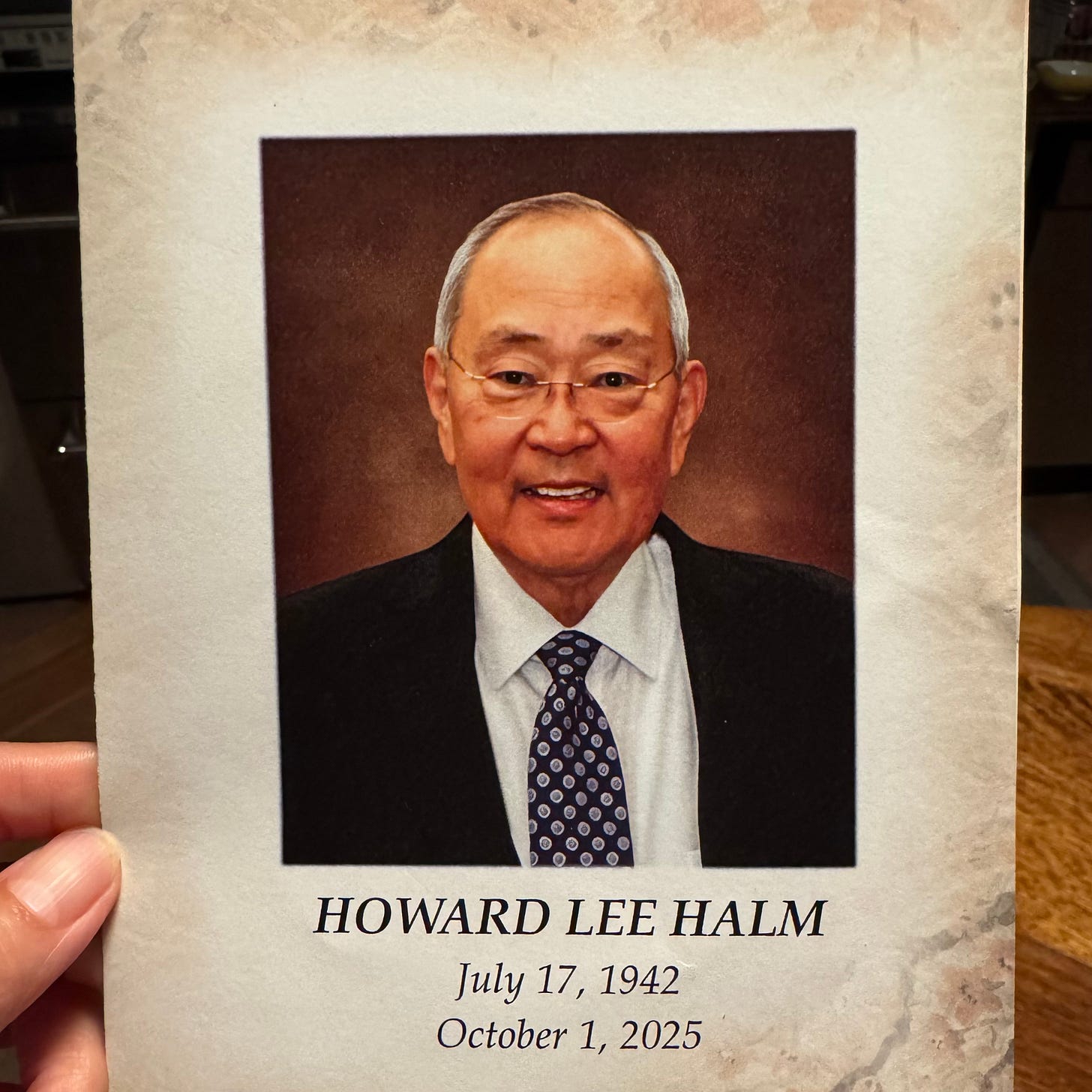

Remembering Howard Halm

When someone you love dies, it never feels real.

Howard Halm was one of the OG Asian American attorneys. His son, David, said this at the service celebrating his life this week. A true original gentleman.

Improbably for a man who spent his extraordinary life as an attorney (a litigator, no less), he was always kind and calm. He met the love of his life, Margaret, when he attended a sorority dance at UCLA. After 55 years of marriage, Howard retired from the law to become her caregiver. He told me about this at the time, in an email, saying that they were still living in the same house they bought in 1974 and enjoying more time with their grandkids.

As usual, though, the purpose of Howard reaching out was not for Howard to talk about himself. He congratulated me on career changes and my kids going to college, he gave me encouragement and feedback on my answers to hostile questioning during confirmation hearings.

No matter what happened throughout the years, I always felt like he was looking out for me.

I first met Howard a few months after I became an attorney in 1994. He was then a named partner at a private law firm, a rare accomplishment for an Asian American attorney even today, but especially so then. I had just graduated from law school, returned home to Los Angeles, taken the Bar, and started a Skadden Fellowship to advocate for low-wage workers at an organization now called Asian Americans Advancing Justice.

And I needed help.

The Koreatown Immigrant Workers Alliance (KIWA) was leading protests at Jessica McClintock’s Beverly Hills boutique. Roy Hong, Paul Lee, and Danny Park were in the early days of building KIWA into what would become one of the most effective worker centers in the nation, organizing mostly Korean and Latino workers who often labored in the same workplaces and experienced the same abuses to stand side by side to change their conditions.

Back then, KIWA was the L.A. arm of a campaign initiated by the Asian Immigrant Women Advocates (AIWA), one of the first to demand that the company that profited from sweatshop labor be held responsible to the garment workers who sewed their clothes, even if the company didn’t hire those workers directly. After the company refused to pay $15,000 in back wages to garment workers who had sewn dresses popular with bridesmaids and prom queens, AIWA and KIWA began protesting at stores to call for corporate responsibility.

Jessica McClintock’s boutique in Beverly Hills was located at the corner of famed Rodeo Drive and Wilshire Boulevard. KIWA understood the power of the contrast between the wealth and luxury symbolized by the location and the poverty and exploitation endured by the workers. They brought together young organizers and college students who showed up in their jeans, t-shirts, and sneakers, with handmade signs. They passed out leaflets to shoppers and tourists.

I joined in some of these actions. They were fun and informative.

For many Asian American organizers and advocates, the experience of being part of “the JM campaign” was formative. One of my favorite chants was “Your dresses, they’re pink, your wages, they stink!”

I still remember one of the most common responses of passersby who stopped to read the leaflet and talk to one of the KIWA organizers or students was, “sweatshops? where?” and their surprise that they were right here in California. Many were shocked that the minimum wage was so low and that, even then, some workers weren’t paid it.

Things escalated when the company sued KIWA to stop the protests. KIWA asked me for help, and I had no idea what to do. The theory I’d learned in law school and the California bar exam courses I’d taken had not prepared me for the reality of practice.

I started making phone calls using a list of attorneys my organization, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, had. And, as luck would have it, one of my first calls was to Howard Halm.

I described the case and the background and Howard immediately agreed to help. It was such a powerful example, so early in my career, of what it means when someone in a position of power says “yes.”

The company’s lawsuit, it turned out, was as much to intimidate as it was based on a viable legal theory. And getting Howard to represent KIWA was a strong message that they weren’t afraid.

I learned a lot from Howard. It was an incredible privilege to see how he approached the case, analyzed options, and assessed risks. He was also unflappable no matter what happened, wasting no time on complaints about the unfairness of the legal system or the outrageousness of the company’s willingness to spend more money on attorneys’ fees than on paying the garment workers. When I raised these things, Howard guided me on staying focused and on devoting our energy to developing the facts and legal theories to defend our client’s interests. From the outset, Howard treated me with tremendous respect, gave criticism gently and praise generously, and valued the perspective I brought as someone who knew our client and had been at the challenged protests. As soon as I passed the Bar, Howard insisted that I appear alongside him at court hearings. It Is impossible to express how much that confidence in and kindness toward me affected my willingness to take on more.

The number of attorneys who can also say this is too many to count. Howard spent his career participating in, building, and leading professional organizations, especially those that opened doors for Asian American attorneys.

He was always aware that his actions would shape how people saw an entire community, and he spent his 56 years in the profession showing what he — and we — could do.

In the end, the lawsuit failed to shut down the campaign. In fact, it backfired. Even more people started showing up at Rodeo and Wilshire to join the protests because we spread the word about how the case showed not only that the company didn’t care about the workers who made their clothes, but also the lengths the company was willing to go to violate other fundamental rights, including the First Amendment.

For Howard, this was a very small pro bono case in a long and impactful career involving thousands of cases. I wish I could tell him now how much his saying “yes” and then throwing himself fully into the case meant to me.

I hope he knew how many young people grew up to be lifelong advocates for justice because he defended their right to raise their voices.

I wish I could thank him for his love, guidance, pride, and example over the years.

At his service, his son Eric talked about how much it meant that Howard officiated his wedding to his husband, a story I had heard from Howard years ago. His grandchildren shared how he showed up for everything—swim meets, birthdays, and graduations, but also dinners, sleepovers, and card games. His legal career is ultimately a small part of all that Howard gave to the world.

Howard showed what it means for someone’s career and his commitment to community to be indistinguishable. In that spirit, in lieu of flowers, Howard’s family encouraged people to donate to Asian Americans Advancing Justice, the same organization with the list of attorneys that brought me and Howard together decades ago. Thank you to our OG. It doesn’t feel real that you’re gone, but in more ways than you can possibly know, you live on.